Inclusive practices are vital to providing students with authentic experiences in diversity and meeting the unique needs of all learners (McGregor & Vogelsberg, 1998; Staub & Peck, 1995). With ongoing collaboration and strategic planning, school communities embrace inclusion by adopting a growth mindset to address student needs. Inclusive schools welcome all local students, with varying performance levels and learning styles, to attend their neighborhood schools, which is why a shared ownership mentality is imperative for success (Janney & Snell, 2013).

Individualized Education Program (IEP) teams often conclude that general education classes are the appropriate placement for students with disabilities. Therefore, school personnel must provide meaningful specially designed instruction (SDI) in that setting through natural opportunities for targeted academic, social, and adaptive skills for these students. When preparing for successful inclusion, it is important to seek a common understanding of the term, and discuss research and practical elements necessary to meet the needs of all students within the school community.

What Is inclusion?

The Inclusive Schools Network defines inclusive education as that in which, “all students are full and accepted members of their school community, in which their educational setting is the same as their nondisabled peers, whenever appropriate” (Stetson & Associates, 2017). Table 1 lists an overview of facts and myths about inclusion.

Table 1

Facts and Myths

|

Inclusion DOES mean: |

Inclusion DOES NOT mean: |

|

|

Adapted from Malatchi (1995).

Why Is Inclusion Important?

When schools faithfully implement inclusive education for students with varied disabilities, all parties involved benefit. Not only does inclusion encourage social interaction for students with disabilities, it can also increase academic outcomes for students without disabilities (Choi, Meisenheimer, McCart & Sailor, 2017; Janney & Snell, 2013). The potential benefits to teaching students with and without disabilities in the same classroom are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2

Demonstrated Benefits of Inclusion

|

Benefits for Students With Disabilities |

Benefits for Students Without Disabilities |

|

|

Aside from student-centered benefits, embracing an inclusive school model ensures compliance with the least restrictive environment (LRE) requirements in Section 612(a)(5) of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (2004), which states “to the maximum extent appropriate, children with disabilities are educated with children who are not disabled.” While the law does not define inclusion, it is a worthy philosophy for students and staff (Pitonyak, 2017). Inclusion, when implemented with fidelity, provides access to meaningful academic and social instruction for all students and promotes acceptance, which is essential as we prepare students to transition as contributing members of society.

How Do I Get Started?

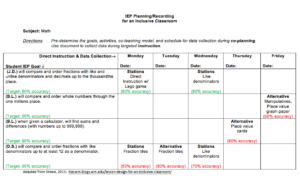

Structural tools are important for shifting inclusion from a philosophical idea to a common practice. One resource that can assist in implementing inclusion for students within the general education setting is the IEP Planning/Recording for an Inclusive Classroom matrix, which is intended for weekly lesson planning and data collection around specially designed instruction.

The example in Figure 1 shows target percentages and results for individualized student goals. The lesson design and formative assessment techniques were determined before instruction was delivered. The data results (shown in red and green) were recorded soon after instruction to allow for analysis to guide further prescriptive planning for explicit instruction on progressing IEP goals.

Figure 1. IEP planning/recording for an inclusive classroom.

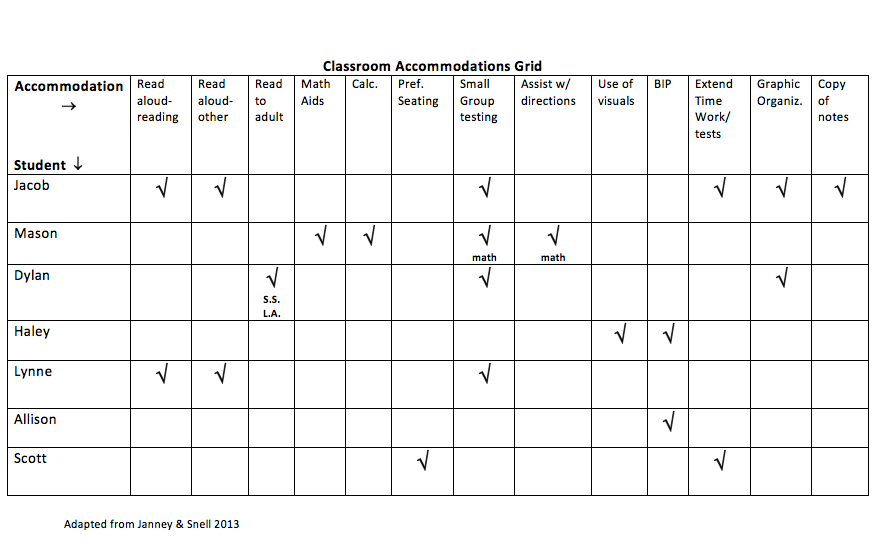

The Classroom Accommodations Grid (see Figure 2) displays an at-a-glance classroom profile of individualized student accommodations used by teachers during planning, instruction, and assessments to ensure that all students with disabilities have access to the general education curriculum. As illustrated, accommodations were listed horizontally at the top with student initials on the side. The special education and general education teachers collaboratively examined student IEPs to determine which accommodations needed to be targeted on the grid.

Figure 2. Classroom accommodations grid.

Research supports inclusive practices as a method of improving outcomes for students (Carter et al., 2005; Choi et al., 1999, Dawson et al., 2017; Wagner et al., 2006). One teacher described the profound urgency of inclusion by sharing a distinctive observation, “Some kids reach out to everybody, but I’ve seen a few kids who have been saved by having somebody to care for in almost an unconditional way” (as cited in Staub & Peck, 1995, p. 3). When educators loyally practice a shared ownership approach to inclusion, it positively influences the quality of life for all students.

Additional Resources

Refer to the following Link Lines articles from T/TAC at the College of William and Mary for additional information on quality indicators for inclusive practices, creating master schedules to support inclusion, and designing lessons for an inclusive classroom.

Access TTAC Online to explore products created by the Real Co-Teachers of Virginia- Middle & High and Real Co-Teachers of Virginia-Elementary, such as co-taught lessons, planning tools, and other resources for including students with disabilities in a co-taught classroom.

View a video testimonial from educator Cyndi Pitonyak on how to move a county to inclusion. Cyndi shares her story as a witness to the success of inclusion in southwest Virginia.

References

Carter, E. W., Cushing, L. S., Clark, N. M., & Kennedy, C. H. (2005). Effects of peer support interventions on students’ access to the general curriculum and social interactions. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 30(1), 15-25. Retrieved from http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.2511/rpsd.30.1.15

Choi, J. H., Meisenheimer, J. M., McCart, A. B., & Sailor, W. (2017). Improving learning for all students through equity-based inclusive reform practices: Effectiveness of a fully integrated schoolwide model on student reading and math achievement. Remedial and Special Education, 38(1) 28-41. doi:10.1177/0741932516644054

Dawson, H., Delquadri, J., Greenwood, C., Hamilton, S., Ledford, D., Mortweet, S., Reddy, S., … & Walker, D. (1999). Class-wide peer tutoring: Teaching students with mild retardation in inclusive classrooms. Exceptional Children, 65(4), 524-536. Retrieved from http://www.mcie.org/usermedia/application/6/inclusion_works_final.pdf

Helmstetter, E., Curry, C., Brennan, M., & Sampson-Saul, M. (1998). Comparison of general and special education classrooms of students with severe disabilities. Education and Training in Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities, 33(3), 216-227. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org.proxy.wm.edu/stable/23879092

Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act, 20 U.S.C. § 612 (2004). Retrieved from http://idea.ed.gov/download/statute.html

Janney, R., & Snell, M. (2013). Characteristics of inclusive schools. In R. Janney & M. Snell (Eds.), Modifying schoolwork (3rd ed., pp. 5, 65). Baltimore, MD: Brookes.

Malatchi, A. (1995). Defining integration. The Collaborator, 4(3). Retrieved from (article no longer available)

Marston, D. (1996). A comparison of inclusion only, pull-out only, and combined service models for students with mild disabilities. Journal of Special Education, 30(2), 121-132. Retrieved from http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/002246699603000201?journalCode=seda

McGregor, G., & Vogelsberg, R. T. (1998). Inclusive schooling practices: Pedagogical and research foundations. A synthesis of the literature that informs best practices about inclusive schooling. Baltimore, MD: Brookes Publishing. Retrieved from http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED418559.pdf

Pitonyak, C. (2017, March 14). Inclusion: What does it mean and who is it for? [Webcast]. Retrieved from https://vcuautismcenter.org/te/webcasts/details.cfm?webcastID=386 VCU Autism Center for Excellence.

Sharpe, M. N., York, J. L., & Knight, J. (1994). Effects of inclusion on the academic performance of classmates without disabilities: A preliminary study. Remedial & Special Education, 15(5), 281. Retrieved from http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/074193259401500503

Staub, D., & Peck, C. A. (1995). What are the outcomes for non-disabled students? Educational Leadership, 52, 36-40. Retrieved from: http://www.ascd.org/publications/educational-leadership/dec94/vol52/num04/What-Are-the-Outcomes-for-Nondisabled-Students¢.aspx

Stetson & Associates, Inc. (2017). Inclusion basics [Web log post]. Retrieved from http://inclusiveschools.org/category/resources/inclusion-basics/

Stowe, M. (2015, September/October). Lesson design for an inclusive classroom. T/TAC Link Lines. Retrieved from http://ttaclinklines.pages..wm.edu/lesson-design-for-an-inclusive-classroom/

Wagner, M., Newman, L., Cameto, R., & Levine, P. (2006). The academic achievement and functional performance of youth with disabilities: A report from the National Longitudinal Transition Study-2 (NLTS2) (NCSER 2006-3000). Menlo Park, CA: SRI International. Retrieved from http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED494936.pdf