Patricia, a 24-year veteran teacher with secondary co-teaching experience in English 9 and Earth Science, poses the following question:

“How do we, my co-teacher and I, deliver a standards-based curriculum in a manner that is accessible and effective for ALL our students including those with disabilities?”

While expectations for student performance have increased over the years, so too has our knowledge of effective instructional practices for use with students in general and special education. For students with disabilities, these instructional strategies are governed by the student’s special education teacher through the student’s Individualized Education Program (IEP). Riccomini, Morano, and Hughes (2017) describe Specially Designed Instruction (SDI) as instruction designed to support a student’s ability to access the general education curriculum while meeting the goals and objectives as outlined in the student’s IEP. The reauthorization of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) 2006 and current IDEA regulations 2012 identify SDI as

adapting, as appropriate to the needs of an eligible child under this part, the content, methodology, or delivery of instruction (i) to address the unique needs of the child that result from the child’s disability; and (ii) to ensure access of the child to the general curriculum, so that the child can meet the educational standards within the jurisdiction of the public agency that apply to all children. (34 C.F.R. §300.39 [b] [3])

According to IDEA, SDI will differ depending upon the needs of individual students with disabilities and may involve any one or all of the components identified in Table 1 (content, methodology, and delivery of instruction).

Table 1. Components of SDI

| Type of Change | Example |

| Content

Note that this does not imply a modification in the standard. On the other hand, it could imply the addition of curriculum such as Braille instruction for a student with visual impairments (Friend, 2018). |

The order in which math multiplication facts are taught to a SWD so as to complement and build upon skills the student already has. Jake, a third grade student with a specific learning disability in math, understands the concept of 5 and is able to skip count without error by 5s up to 100. Therefore, the concept of multiples and the study of multiplication facts is introduced with the 5s instead of the 2s, 3s, or 4s. |

| Methodology

Modifications made to the type of instruction used. In some cases, varied and unique instructional approaches that are not generally employed with same age or grade peers (Friend, 2018). |

Angela, a student with a disability who struggles with reading comprehension, receives instruction in the Strategic Instruction Model (SIM), The Fundamentals of Paraphrasing and Summarizing. Learning this strategy systematically and sequentially enables Angela to acquire the skills needed to identify a topic sentence, main idea, and supporting details. |

| Delivery of instruction

Delivery can refer to the location of the instruction, group size, and any other condition employed to maximize a student’s learning outcomes (Friend, 2018). |

One-on-one instruction via a structured, sequential, multi-sensory approach to teach decoding (e.g., Orton-Gillingham, Wilson Reading System). |

The Council for Exceptional Children and the Collaboration for Effective Educator Development, Accountability, and Reform (CEEDAR) Center identify 22 fundamental, research-based teaching practices referred to as high-leverage practices, or HLPs (see Table 2), that should be evident in any K-12 classroom (McLeskey, J., Barringer, M. D., Billingsly, B., Brownell, M., Jackson, D., Kennedy, M.,… & Ziegler, D., 2017). These practices aid student learning across tiers of support and educational settings. The HLPs address four interrelated components of special education: collaboration; assessment; social, emotional, and/or behavioral practices; and instruction. For several practices, links to additional resources are provided.

Table 2. High-Leverage Practices, CEC & CEEDAR Center (2017)

| Collaboration | HLP 1 | Collaborate with professionals to increase student success. |

| HLP 2 | Organize and facilitate effective meetings with professionals and families. | |

| HLP 3 | Collaborate with families to support student learning and secure needed services. | |

| Assessment | HLP 4 | Use multiple sources of information to develop a comprehensive understanding of a student’s strengths and needs. |

| HLP 5 | Interpret and communicate assessment information with stakeholders to collaboratively design and implement educational programs. | |

| HLP 6 | Use student assessment data, analyze instructional practices, and make necessary adjustments that improve student outcomes. | |

|

Social/ Emotional/ Behavioral Practices |

HLP 7 | Establish a consistent, organized, and respectful learning environment. |

| HLP 8 | Provide positive and constructive feedback to guide a students’ learning and behavior.

|

|

| HLP 9 | Teach social behaviors. | |

| HLP 10 | Conduct functional behavioral assessments to develop individual student behavior support plans. | |

| Instruction | HLP 11 | Identify and prioritize long- and short-term learning goals. |

| HLP 12 | Systematically design instruction toward specific learning goals. | |

| HLP 13 | Adapt curriculum tasks and materials for specific learning goals. | |

| HLP 14 | Teach cognitive and metacognitive strategies to support learning and independence. | |

| HLP 15 | Provide scaffolded supports. | |

| HLP 16 | Use explicit instruction.

|

|

| HLP 17 | Use flexible grouping. | |

| HLP 18 | Use strategies to promote active student engagement. | |

| HLP 19 | Use assistive and instructional technologies. | |

| HLP 20 | Provide intensive instruction. | |

| HLP 21 | Teach students to maintain and generalize new learning across time and settings. | |

| HLP 22 | Provide positive and constructive feedback to guide students’ learning and behavior. |

Note. Reprinted with permission from Big Ideas in Special Education Specially Designed Instruction, High-Leverage Practices, Explicit Instruction, and Intensive Instruction, by Riccomini, P. J., Morano, S, and Hughes, C. A. Retrieved from TEACHING Exceptional Children, Vol. 50. No. 1, pp. 23. Copyright 2017 by The Author(s).

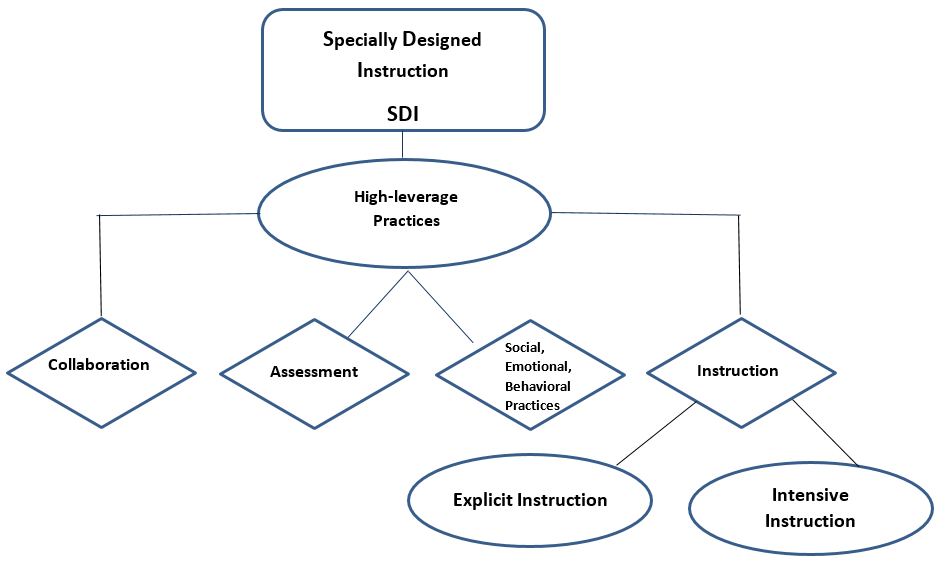

HLPs are a starting point for the selection, design, and implementation of SDI in light of a student’s special learning needs (Riccomini et al., 2017). Explicit and intensive instruction are two HLPs under Instruction, and are hallmarks of SDI (McLeskey et al., 2017; Riccomini et al., 2017) (See Figure 1). More discussion and examples of explicit and intensive instruction are provided below.

Figure 1. Specially Designed Instruction and High-Leverage Practices

Explicit instruction is clear and outcome-driven. It is systematic and sequential, thereby reducing cognitive confusion, allowing students to focus their energy on one concept at a time. Teachers engage students by offering varied opportunities to respond, providing positive and targeted feedback, and preparing thoughtfully planned practice (McLeskey et al., 2017; Riccomini et al., 2017).

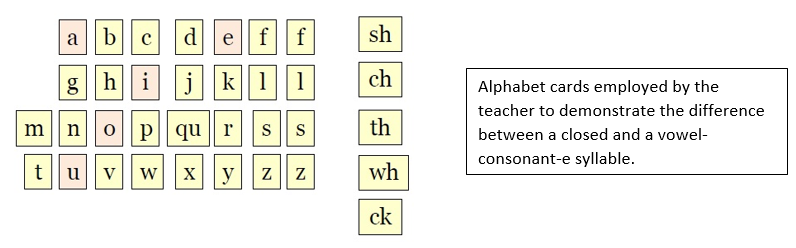

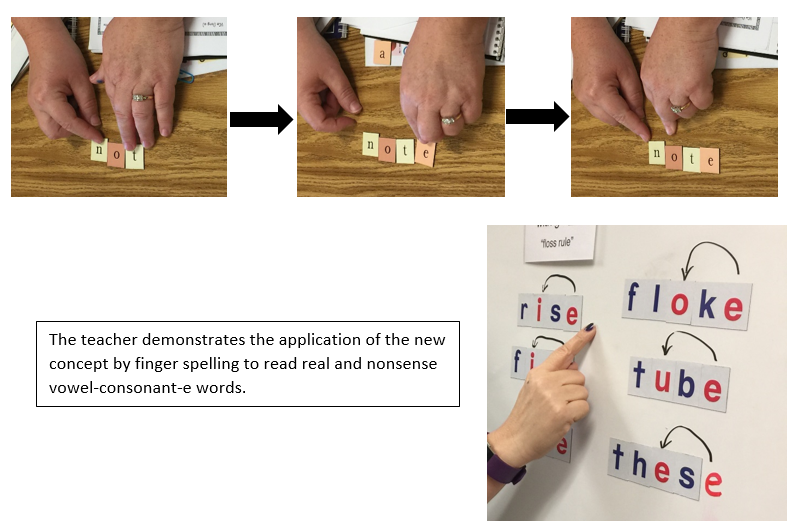

In the example below, a special education teacher working with a group of second grade students employs the principles of explicit instruction to introduce the vowel-consonant-e syllable type. Having already taught her students the concept of the short vowel closed syllable, the teacher uses colored-coded alphabet cards to teach the new syllable type. She states the rule directly, explaining that the “e” remains silent but signals a long vowel sound. The teacher employs finger spelling to demonstrate the reading of several words using an ‘I do’ approach as her students watch and listen. Next, she provides an opportunity for her students to practice the new concept as she works in tandem with them (we do) to read several carefully selected words. The teacher balances confirming and corrective feedback throughout the process. Finally, she encourages her students to independently practice decoding vowel-consonant-e words from a third list (you do). Once students have demonstrated mastery of reading one-syllable words comprised of vowel-consonant-e syllables, the teacher moves her students to the next level of mastery. Figure 2 below illustrates the color-coded alphabet cards used by the teacher to explicitly teach the vowel-consonant-e syllable.

Figure 2. Color-coded alphabet cards employed by the teacher.

Teachers use intensive instruction to match the severity of student need and close gaps between student performance and expected outcomes. Teachers target a small number of clearly articulated, high priority skills and concepts critical for academic success. Instruction may be intensified in a number of ways including reducing group size such that students with similar needs are grouped together. Groups may meet more often or for longer periods of time during the school day. Students then have more opportunities to learn and practice skills with immediate, corrective feedback. Instruction may also be intensified by providing more detailed explanations, modeling, and learning opportunities with visuals, manipulatives, and/or think-alouds; breaking instruction or tasks into smaller steps; and offering increased initial support that is gradually faded over time. IEP teams base decisions related to the frequency and intensity of the instruction delivered on a student’s performance data. Intensive instruction is considered a Tier 3 level intervention, and is delivered by special educators (McLeskey et al., 2017). For ideas on intensifying instructional delivery during guided reading follow this link.

In the example above, the teacher would monitor students’ progress via formative assessments to guide her daily instruction and to ensure that each student reaches the established instructional targets. If a student’s progress stalls, the IEP team would revisit the intervention and make adjustments.

The statements in Table 3 are intended to guide special educators in identifying and planning SDI and to determine if students with disabilities are receiving appropriate instruction (Friend, 2018).

Table 3. Checklist for Identifying SDI

|

✓ if ‘Yes’ |

Guiding Statements |

| 1. Teachers use a student’s present level of performance to target instruction. | |

| 2. The instruction allows students to learn in spite of their disability. | |

| 3. Instruction is data-driven from planning to assessment. | |

| 4. Instruction is evidence- and research-based. | |

| 5. Instruction is systematic in its planning, delivery, and evaluation. | |

| 6. The instruction differs from an accommodation in that a teacher directly delivers the lesson. | |

| 7. The student needs the selected approach while other students do not. | |

| 8. The instruction supports the student in reaching the standard without modifying or reducing the standard (unless the IEP team determines standard modification is required based upon significant student need). | |

| 9. Instruction addresses a wide variety of domains including academic, behavior, social skills, communication skills, and vocational skills. | |

| 10. Generalization and maintenance are explicitly taught. |

Note. Reprinted with verbal permission from Effective and sustainable co-teaching: Going beyond the basics, by Friend, M. Retrieved from handout. 2018, May.

Educators like Patricia and her co-teacher, should consider the 22 HLPs as outlined by McLeskey et at. (2017) when designing SDI for individual students. The IEP team determines if intensive intervention is necessary, and if so, identifies appropriate interventions and accommodations through consideration of a student’s strengths, specific learning needs, and the extent of academic gaps. The team then specifies the frequency and intensity of the instruction to be delivered and decides what evidence will be used to demonstrate proficiency. The process of planning and delivering SDI to address the unique needs of students with disabilities enables IEP teams to close academic gaps and move students forward.

References

Education for All Handicapped Children Act of 1975, Pub. L. 94-143, 89 Stat. 773, codified at 20 U.S.C. § 1400

Friend, M. (2018, May). Effective and sustainable co-teaching: Going beyond the basics. Paper presented at the Virginia Department of Education’s Training and Technical Assistance Center (T/TAC) at Old Dominion University’s Conference for Co-teaching teams. Portsmouth, VA.

Individuals With Disabilities Education Act, 20 U.S.C. §§ 1400 et seq. (2006 & Supp. V. 2011)

Individuals With Disabilities Education Act regulations, 34 C.F.R. § 300 (2012)

McLeskey, J., Barringer, M. D., Billingsly, B., Brownell, M., Jackson, D., Kennedy, M.,… & Ziegler, D. (2017). High-leverage practices in special education. Arlington, VA: Council for Exceptional Children & CEEDAR Center.

Riccomini, P. J., Morano, S., & Hughes, C. A. (2017). TEACHING Exceptional Children, 50(1), 20-27.