Adam is six years old. Six months into his kindergarten year, Adam’s teachers and administrators are concerned. He is not demonstrating growth toward meeting the state and national benchmarks for kindergarten, and he struggles with even the most basic reading, math, expressive language, and social skills. He also appears not to have the basic prerequisite skills for kindergarten, such as attending, following simple directions, and getting along with peers. He cries frequently and states, “I hate school! I am STUPID!”

It is the morning of the school’s Child Study Team meeting, and all seated around the table appear anxious and concerned. The team is gathered to discuss retention of Adam in kindergarten.

In a neighboring school division, 10-year old Sarah has been identified as a student with Specific Learning Disabilities and Speech and Language Impairment. Areas of concern include reading (decoding and fluency), auditory processing, and articulation. Her Individualized Education Program (IEP) indicates that she demonstrates many of the characteristics of dyslexia and reads at a beginning second-grade level. She is in a co-taught fifth-grade class and receives small-group instruction and support from her special education, speech-language, and classroom teachers. She qualifies for the read-aloud accommodation on all classwork assignments and assessments as well as for state and district testing.

Her IEP team is convened to discuss retaining Sarah in fifth grade due to her reading level, lack of success on SOL tests, and the increased expectations of the middle school curriculum.

The above scenarios are commonplace in both public and private schools. Grade retention is the practice of requiring a student who has completed a year’s worth of schooling in a particular grade to return the following year and repeat that grade’s academic content for a second time (Dombek & Connor, 2012; Vandecandelaere, Vansteelandt, Fraine, & Van Damme, 2016). Each year, 2.4 million students are retained in American schools (Davoudzadeh, McTernan, & Grimm, 2015).

A student’s failure to meet academic expectations in one or more areas, failure to succeed on high-stakes tests, failure to demonstrate mastery of grade-level content, immaturity, or age are commonly articulated reasons for grade retention (Dombek & Connor, 2012). The underlying assumption for retention, therefore, is that revisiting the academic content and having an extra school year to develop and mature is a viable means of “closing the gap” and improving a low-performing and low-achieving student’s academic skills (Davoudzadeh et al., 2015).

The literature and research on grade retention is expansive (Andrew, 2014; Davoudzadeh et al., 2015; Dombec & Connor, 2012; Moser & West, 2012) and controversial. Gender, ethnicity, family socioeconomic status, parents’ level of education, and the individual student’s academic potential and skills are known predictors of grade retention (Davoudzadeh et al., 2015). For students with disabilities, some view grade retention as being in direct opposition to the underlying premises of IDEA (Perez, 2014).

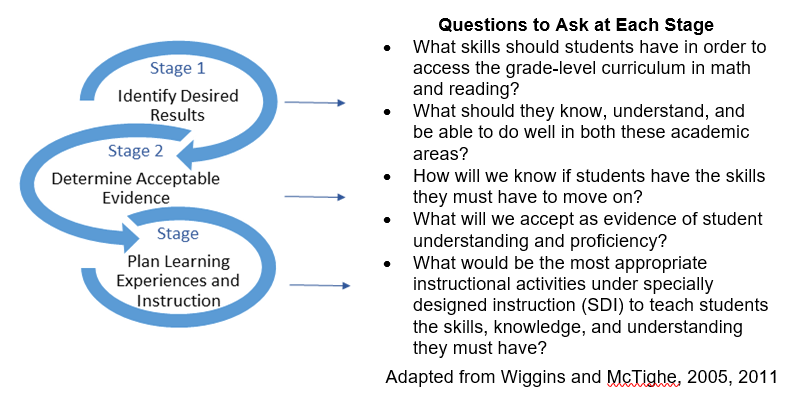

Understanding by Design, which utilizes backward design, a way of “thinking more purposefully and carefully about the nature of any design that has understanding as the goal” (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005, p. 7), offers a process for identifying alternatives to retention for struggling students. Understanding by Design is not a program or a prescriptive recipe. It is an approach based on the following:

- Thinking purposefully about curricular and instructional planning in light of desired outcomes;

- Developing deeper student understanding as evidenced by a student’s ability to apply his or her learning and to transfer learning to new and varied situations (i.e., generalization);

- Unpacking and transforming content and, in some cases, behavioral standards into meaningful Stage 1 questions and appropriate Stage 2 assessments (see Figure 1);

- Planning effective curriculum for achieving long-term desired results through a three-stage design process (see Figure 1);

- Teachers frequently checking for successful meaning making and transfer of learning by the student; and

- Frequent reviewing to assess the quality and effectiveness of instructional units.

Understanding by Design involves a continuous-improvement approach to attainment of the learning goals. The results of each instructional design (student performance) informs adjustments made to both the curriculum and instruction. This implies a regular and consistent cycle of analyze, adjust as needed, instruct, reevaluate; analyze, adjust as needed, and so on (Wiggins & McTighe, 2011).

Figure 1. Three stages of backward design.

When planning for students who might be considered for retention, teams may instead employ a backward-design approach. The principles of backward design allow teams to prioritize and establish specific exit skills that a student must demonstrate for success in the general education curriculum. Clearly articulated learning outcomes lead to long-term goals, which are documented in a student’s IEP. The IEP team then articulates evidence for mastery. Finally, the IEP team plans for student success by determining the SDI needed to address the student’s learning needs.

Students with disabilities often present as struggling learners early in their academic careers. Adam, for instance, struggles both academically and behaviorally in kindergarten. By considering the reading, writing, math, and social skills required for entering first grade, the Child Study Team could use a modified backward-design approach to identify desired results, determine acceptable evidence, and plan specific instruction for Adam. For example, the team and teachers at Adam’s school might consider behavioral interventions such as small-group or one-on-one social skills training. This training could be paired with short-term behavior goals accompanied by positive rewards to shape Adam’s attending, following simple directions, and interacting positively with his peers. Additionally, Adam’s kindergarten teacher could receive support from the speech-language specialist and the reading specialist to plan for specific instruction to address reading and expressive language skills. Documenting interventions, SDI, and adjustments made to the delivery of instruction and the materials used would shed light on issues related to how Adam learns best, what he responds to, and how to plan for further instruction to move him forward. Teachers could then plan for the provision of supports to help Adam progress through kindergarten and into his first grade year and beyond.

Sarah, in our other example above, might require intensive small-group or one-to-one explicit reading instruction using an evidence-based multisensory approach, in addition to speech and language services. With this SDI in place, Sarah’s reading deficits, decoding and fluency, would be addressed and remediated, enabling her to access the general education curriculum more independently.

In most instances, by the end of the primary grades, educators have a clear picture of a student’s strengths and weaknesses, special learning needs, and areas of difficulty that require explicit, intensified instruction. With knowledge of national, state, and division grade-level skill requirements, Child Study and IEP teams could consider a modified backward-design approach in conjunction with specially designed explicit, systematic, and intensive instruction in lieu of grade retention. This approach supports direct remediation of skill deficits, leading to skill mastery and student success.

References

Andrew, M. (2014). The scarring effects of primary-grade retention? A study of cumulative advantage in the educational career. Social Forces, 93(2), 653-685.

Davoudzadeh, P., McTernan, M. L., & Grimm, K. J. (2015). Early school readiness predictors of grade retention from kindergarten through eighth grade: A multilevel discrete-time survival analysis approach. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 32, 183-192. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2015.04.005

Dombek, J. L., & Connor, C. M. (2012). Preventing retention: First grade classroom instruction and student characteristics. Psychology in the Schools, 49(6), 568-588. doi:10.1002/pits.21618

Moser, S. E., West, S. G., & Hughes, J. N. (2012). Trajectories of math and reading achievement in low-achieving children in elementary school: Effects of early and later retention in grade. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104(3), 603-621. doi:10.1037/a0027571

Perez, E. L. (2014). Disability and power: A charter school case study investigating grade-level retention of students with learning disabilities. LMU/LLS Theses and Dissertations, 206. http://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/etd/206

Vandecandelaere, M., Vansteelandt, S., Fraine, B. D., & Damme, J. V. (2016). The effects of early grade retention: Effect modification by prior achievement and age. Journal of School Psychology, 54, 77-93. doi:10.1016/j.jsp.2015.10.004

Wiggins, G. P., & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by design – Expanded 2nd edition. Alexandria, VA: ASCD

Wiggins, G. P., & McTighe, J. (2011). Understanding by design guide to creating high-quality units. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.